b l o g

f e b r u a r y 2 0 2 1

Royal Status – pineapples were also known as King or Queen Pine IMAGE: Getty Images

Royal Status – pineapples were also known as King or Queen Pine IMAGE: Getty Images

By Bethan Bell, BBC News

Symbols have always been used to signal one’s status. Military insignia, family signet rings and heirloom watches; impressive properties filled with original art, expensive cars and designer handbags ensure a luxury lifestyle is obvious to all. But for about 250 years, all of these signposts of wealth and good breeding were ably fulfilled by … the pineapple.

Centuries before even the man from Del Monte said “yes”, the country’s must-have accessory graced the table at the very richest aristocrats’ social gatherings.

But the scaly sweet was too valuable to eat – a single fruit was worth thousands of pounds and often the same pineapple would be paraded from event to event until it eventually went rotten.

Later, a roaring trade in pineapple rental developed, where ambitious but less well-off folk might hire one for a special event, dinner party or even just to jauntily tuck under an arm on a show-off stroll.

Margaret Thatcher (L) and a pineapple IMAGE: David Ashdown

Margaret Thatcher (L) and a pineapple IMAGE: David Ashdown

By the 1770s, “a pineapple of the finest flavour” became a phrase used for anything that was the best of the best. It’s played upon in Sheridan’s 1775 play The Rivals, when Mrs Malaprop confuses the word with “pinnacle” and exclaims: “He is the very pineapple of politeness!”.

In a television adaptation of Jane Austen’s unfinished Regency novel Sanditon, Lady Denham’s grand luncheon has a pineapple in pride of place – although it is cut to reveal the inside is full of maggots, demonstrating the vast wealth of the character but also the transitory nature of the status symbol.

The orangery at Hanbury Hall has carved pineapples on its roof, but only the very wealthiest could afford a pinery IMAGE: Philip Halling

The orangery at Hanbury Hall has carved pineapples on its roof, but only the very wealthiest could afford a pinery IMAGE: Philip Halling

The idea that pine apples (as they used to be known) are somehow associated with wealth and status is fairly well-established for those of us who enjoy a trip to a stately home.

Engravings can be admired on corbels and finials across the UK, remnants of a time when keeping up with the neighbours meant throwing lavish parties and displaying one’s riches.

The 16th and 17th Centuries saw a number of exotic foods brought back to Europe from the New World and Asia – and the pineapple became most associated with prestige and luxury.

According to Dr Lauren O’Hagan from Cardiff University’s School of English, Communication and Philosophy, “the pineapple was previously unknown in the Old World, so it was free of the cultural resonances of other fruits, which enabled people to create new meanings from it”.

For example, the apple was already associated with the forbidden fruit in the Garden of Eden, while pomegranate seeds kept the Greek goddess Persephone in the underworld for half the year.

Artist Hendrick Danckerts painted Charles II being presented with a pineapple by the King’s Gardener, John Rose IMAGE: Heritage Images

Artist Hendrick Danckerts painted Charles II being presented with a pineapple by the King’s Gardener, John Rose IMAGE: Heritage ImagesThe fruit even attracted a nickname: “King Pine”. And actual kings were keen to hop on the gilded bandwagon.

John Parkinson, Royal Botanist to Charles I, described the pineapple in theTheatrum Botanicum as “scaly like an artichoke” but “so sweet in smell… tasting … as if wine, rosewater and sugar were mixed together.”

Charles’ son and successor Charles II was so taken with pineapples that he commissioned a portrait of himself being presented with one – it was purported to be the very first to be grown in England, at Dorney Court in Berkshire, but it’s now thought to have been imported as a juvenile and merely ripened on home soil.

A stand would display a not-for-eating pineapple in the centre of a platter of cheaper fruits IMAGE: Carolyn Stoddart-Scott

By the Georgian era, pineapples were starting to be cultivated in Britain. Perhaps surprisingly, the fact that they could now be grown in situ did not decrease the fruit’s cachet, but rather enhanced it.

Waiting for a pineapple to be transported from the tropics was one thing; having the facilities and staff skilled enough to grow one at home was quite another, becoming a hobby carried out exclusively by the landed aristocracy.

The Gentleman’s Magazine of 1764 estimated that it cost £150 (according to the Bank of England’s inflation calculator, roughly equivalent today to £28,000) to build a hothouse, cover the annual running costs and buy the plant stock. And this expense was not guaranteed to give any return.

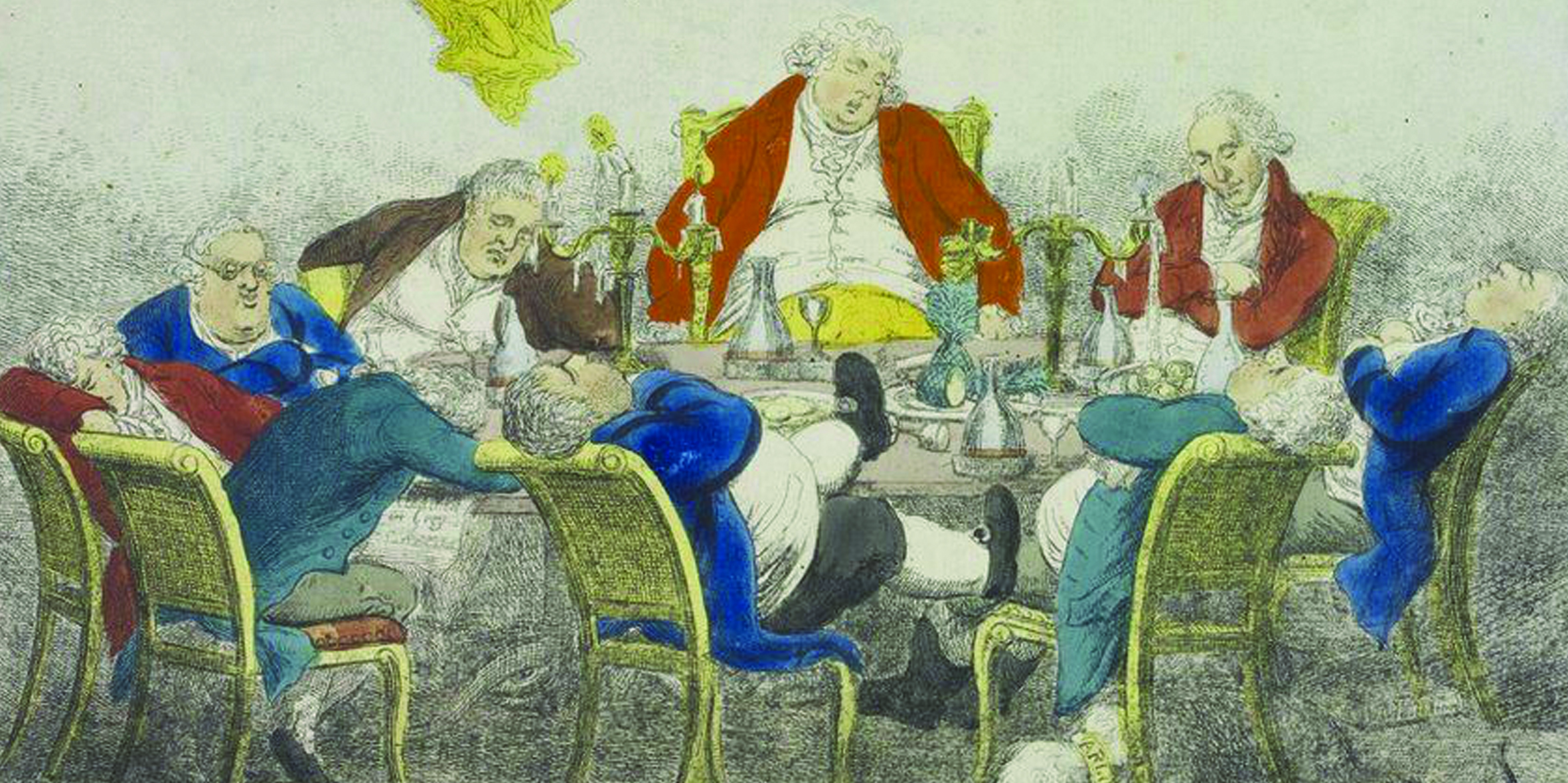

The Cabinet Dinner, or a Political Meeting by Charles “Argus” Williams, shows partly eaten pineapples abandoned on the table – indicating the wealth and wastefulness of the upper classes IMAGE: V & A Museum

The Cabinet Dinner, or a Political Meeting by Charles “Argus” Williams, shows partly eaten pineapples abandoned on the table – indicating the wealth and wastefulness of the upper classes IMAGE: V & A Museum

“Heating in glasshouses during the mid 17th Century was provided by furnaces placed within the structure, but fumes often damaged or killed the plants,” Ms Lausen-Higgins says.

“Later, ‘fire walls’ were heated by hot air rising from furnaces or stoves which required constant stoking with coal. This was a dangerous method and many early ‘pineries’, as they later became known, burned down.”

On top of the risks of one’s pineapple investments going up in smoke, it took several years for the fruit to bloom.

A pineapple which had overcome all those hurdles was scarce enough to be valued at £60 (roughly £11,000). It was even better if it had shoots and leaves still on it, making it clear that it was homegrown.

People even started to carry pineapples under their arm as a sign of status, according to Dr O’Hagan

Concerned about wasting such high-value fruit by eating it, owners displayed pineapples as dinnertime ornaments on special plates which would allow the pineapple to be seen and admired but surrounded by other, cheaper, fruit for eating.

These pineapples were expensive enough to warrant security guards, and maids who transported them were considered to be at great risk of being targeted by thieves.

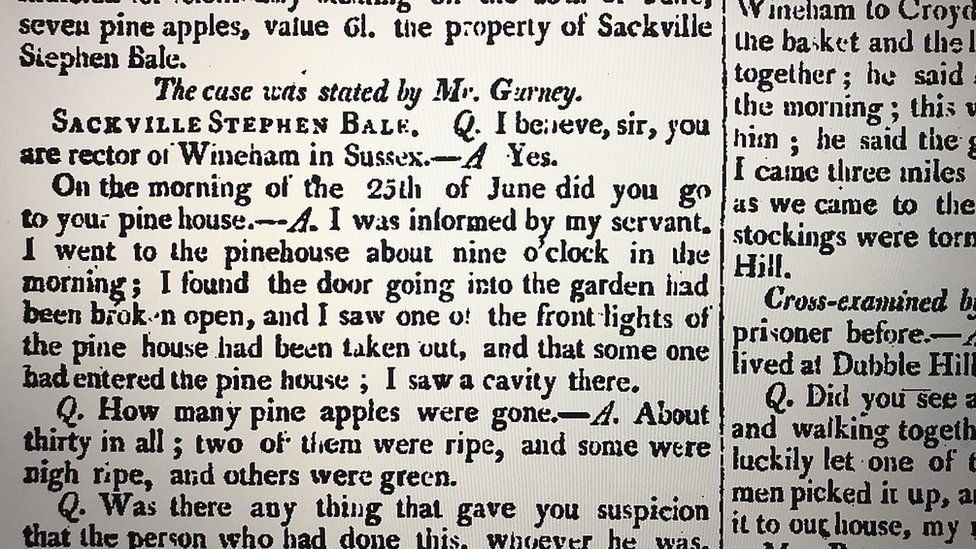

The 1807 Proceedings of the Old Bailey show several cases for pineapple theft, Dr O’Hagan points out, including that of a Mr Godding who was sentenced to seven years transportation to Australia for stealing seven pineapples.

A transcription from a 1807 court case indicates the monetary value of pineapples

A transcription from a 1807 court case indicates the monetary value of pineapples

Because the ever-aspiring middle classes were anxious to get their mitts on the fruit but could not afford to cultivate or buy them, canny businessmen opened pineapple rental shops across Britain. Companies began to cash in on the fruit’s popularity and as with many crazes, the market for pineapple-themed goods exploded.

Porcelain-makers Minton and Wedgwood started producing pineapple-shaped teapots, ewers and jelly moulds. Ornately carved clock cases, bookends and paintings extended the trend from the dining table to other rooms in the house.

Outdoors, the pineapple was represented on carriages and garden temples. After all, if the fruit itself would not last, carved-stone pineapples on plinths would certainly be a lasting reminder to guests and passers-by of the wealth within a manor house.

The English passions of subtly demonstrating wealth and having a nice cup of tea were united in this pineapple-finialed teapot IMAGE:Carolyn Stoddart-Scott

But this superstar status was not to last much longer. Steamships started to import pineapples to Britain regularly from the colonies and the prices consequently dropped.

And it wasn’t just the middle classes who could afford a pineapple, but – horror of horrors – the working classes could too.

“What was once considered a luxury fruit could now be found cheaply on stalls and barrows in most cities and towns across the country,” says Dr O’Hagan. “At this time, working-class people eating pineapples even became used in satirical prints as a visual metaphor for the problem of progress.”

A man selling pineapples for 9d – cheaper than potatoes, but maybe not as versatile iMAGE: Topical Press Agency

A man selling pineapples for 9d – cheaper than potatoes, but maybe not as versatile iMAGE: Topical Press Agency

The pineapples so worshipped in earlier times were not only out of favour, but were becoming homogenised. In 1835, horticulturist Sir David Munro listed 52 varieties of pineapple.

Ms Lausen-Higgins says that only five strains remain in cultivation today, and of those, only the Smooth Cayenne and Jamaica Queen are readily available.

“From the 1950s onwards, pineapples were bred so that they fitted neatly into a tin. Fruits with a characteristically pyramidal shape, such as Black Prince, became extinct.”

However, some traces of Britain’s eccentric love affair with the pineapple remain.

The craze for pineapple-themed goods remains strong IMAGE: Johannes Eisele

The craze for pineapple-themed goods remains strong IMAGE: Johannes Eisele

The Lost Gardens of Heligan in Cornwall has traditional pineapple pits, heated by decomposing manure. As in times past, growing the fruit is labour-intensive and time-consuming – it takes about seven years to grow a pineapple.

The gardens estimate that restoration and maintenance of the pit, fine-tuning of the growing methodology, and the man hours to look after the fruit means “each pineapple probably cost us in excess of £1,000”.

Despite this hefty price tag, Heligan’s 15-strong team of gardeners continues to produce the tropical fruit. In summer 2019, the first Smooth Cayenne to fruit at Heligan in more than two years was harvested.

Staff at the Lost Gardens of Heligan shared the fruit that took seven years to grow IMAGE: Lost Gardens of Heligan

Staff at the Lost Gardens of Heligan shared the fruit that took seven years to grow IMAGE: Lost Gardens of Heligan

And King Pine is still gracing royal palates.

The second pineapple harvested at the gardens was given to the Queen (the first was tasted by staff in case it tasted like manure. It did not) and Prince Charles went to the gardens in 1997 to have a look at the first budding plant.

Prince Charles looking at King Pine IMAGE: Heligan

Prince Charles looking at King Pine IMAGE: Heligan

Once the pineapple was on the menu for ordinary people and therefore off the menu for the nobility, the upper classes sought new ways to distinguish themselves from the masses.

Did they learn their lesson from the short-lived status and money-sucking nature of the pineapple? Maybe they could have invested in precious gems or impressive property.

No, they didn’t. Dr O’Hagan says the truly wealthy then set their caps at another luxury and difficult-to-grow food.